Why Dairy Makes a Great Recovery Sports Drink: All About Rehydration and Sweating

After a hard workout what do you need for a great post workout drink? You need a drink that facilitates rehydration, rebuilds damaged tissues and refuels depleted energy stores. Dairy, yogurt and milk drinks address these concerns better than other types of sports drinks. Here's the lowdown on why a milk mustache can help you rehydrate.

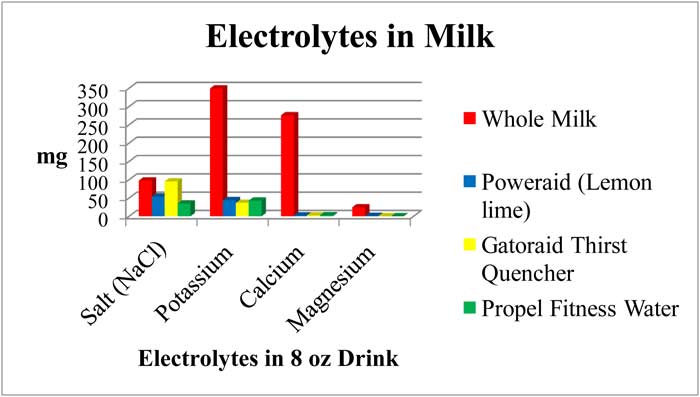

Drinking down dairy smoothies can help replenish electrolytes lost when you perspire. Compare the electrolytes found in one cup of milk to those found in several sports drinks below. The five key electrolytes for endurance athletes are sodium, chloride, potassium, calcium and magnesium. All nutritional data was obtained from USDA SR-21:

As you can see from the chart above, milk has an similar amount of salt (sodium and chloride) when compared to Poweraid, Gatoraid Thirst Quencher and Propel Fitness Water. Where whole milk really pulls ahead of the pack is with its high amount of potassium, calcium and magnesium. Replenishing these electrolytes is vital during high intensity activity.

Moa et al. (2001) reported that male soccer players lost 1,896 mg sodium, 248 mg potassium, 20 mg calcium and 52 mcg iodine in sweat following a 1-hr game (magnesium was not evaluated). Milk contains between 30-100 mcg iodine per 1 cup (it varies depending on diet and time of year).

Why do you need electrolytes anyway?

Electrolytes are negatively or positively charged ions that conduct electrical activity. They develop an electrical charge when dissolved in water. Positively charged electrolytes are called cations. They include potassium (K+), sodium (Na+), calcium (CA++) and magnesium (Mg++). Negatively charged electrolytes are called anions. They include chloride (Cl-) and bicarbonate (HCO3-).

Picture: Caution! It is important to replace electrolytes when exercising.

Check out what these electrolytes do on our Milk Sports Drink page. These ions are used in the human body to maintain fluid balance, help muscles contract, maintain blood pressure and facilitate nerve activity (including brain activity).

Electrolyte balance is extremely important. Your body regulates fluid and electrolytes homeostasis within the body closely. It uses a complex system which includes stimulating thirst, hypothalamus sensing of blood osmolarity, pituitary glands, hormones release and kidney regulation of urine and electrolyte release.

What Works Best for Rehydration?

Electrolytes and carbohydrates mixed in water help your body rehydrate after exercise better than just electrolyte alone. Recent studies have suggested that a drink containing electrolytes, carbohydrate, proteins and fats is better than one containing just electrolytes and carbohydrates. Drinking milk after exercise rehydrated subjects quicker and resulted in better fluid retention when compared to drinking a standard sports drinks, a carbohydrate solution or water (Shirreffs et al 2007, James et al. 2011, James et al. 2013).

If you are exercising really hard or running a long marathon rehydrate with a mix of water and nutrients. It can be dangerous to drink too much plain water during long hard exercise. Over hydration will dilute the available electrolytes in the body which can cause hyponatremia and/or water intoxication. Hyponatremia occurs when sodium concentrations decline in the body. Symptoms of hyponatremia can include headache, irritability, confusion, nausea, muscle cramping and fatigue. People may start acting 'drunk' and thinking is impaired. In severe cases seizures, brain damage, coma or death can result.

Sodium is a positively charged ion that helps maintain proper water balance within the body. Low concentrations of electrolytes such as sodium in the blood changes the osmotic balance in the body. In very simple terms, water is attracted to electrolytes Since electoral concentration is lower in the blood and fluid outside the cells, fluids flow into the cells which have more electrolytes. The cells swell up with excess water. In the brain, cell swelling causes intracranial pressure which results in headaches and erratic behavior.

Why do you need to rehydrate?

Fluid loses as small as 1-2% can cause performance to drop. Losing 4% or more of your fluid can cause coma and death.

The forgotten electrolyte: Magnesium

Many athletes forget to replenish magnesium! Low magnesium concentrations can result in poor performances. Magnesium is critical to make energy (ATP), transmit nerve impulses and contract muscle. Magnesium deficiency can cause muscle cramps, confusion, irregular heartbeat, and a frazzled and anxious mood. Longer and more intense exercise result in more magnesium and calcium loss in sweat.

Milk is an ideal rehydration drink.

Milk was equal to a carbohydrate-electrolyte solution in its ability to rehydrate men who were exercising to exhaustion in a humid and hot environment (Watson et al. 2008). In addition, those consuming a carbohydrate-electrolyte solution were in a negative potassium balance. Shirreffs et al. (2007) found that drinking milk after exercise rehydrated subjects longer than a sports drink or water. Subjects drinking milk also lost less water due to urine than did those consuming an equivalent amount of water or sports drink. Milk drinkers had about half of the urine volume as those drinking water or traditional sports drinks. This may be due to the milk protein (James 2012). Personally, I think that there are some athletic events where needing to pee less could be a big advantage.

Milk drinkers in these studies remained in net positive fluid balance throughout their recovery while those drinking water or sports drinks returned to net negative fluid balance (Shirreffs et al. 2007, Watson et al. 2008). Other studies found that a carbohydrate milk protein drink was better absorbed and retained in dehydrated men when compared to a energy and electrolyte matched carbohydrate solution (James et al. 2011). Milk protein was more effective than carbohydrates at augmenting fluid retention (James et al. 2011, James et al. 2013).

Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Sweat

Picture: Beef cattle work up a sweat in a fun walk run event. Normally cattle forgo the event T-shirts.

What nutrients are lost in sweat?

When you work out hard you lose water and minerals in sweat. Electrolytes lost include salt (sodium chloride), potassium, magnesium and calcium. Other nutrients you lose in much smaller amounts are iron, copper, zinc, iodine, amino acids and water-soluble vitamins like B-complex vitamins and vitamin C. Heavy sweaters can lose 1-8% of their weight in fluid loss (Sharp 2006).

What can happen when you lose electrolytes in sweat?

Symptoms of electrolyte loss can include muscle cramping, dizziness when standing (due to low blood pressure), restless legs at night or impaired thinking. Electrolyte loss depends on the individual, environment, duration and intensity of exercise, body composition, fitness and gender.

Do people lose nutrients in sweat at different rates?

Yes, there can be a lot of difference in nutrient loss during sweating. Some people sweat out a lot of salt. If your skin tastes salty after exercise or your clothes have a salty residue from sweat you are losing more salt. It is important for you to add salt to your post workout diet. Another warning sign that you need to add electrolytes is if you have muscle cramping during or after exercise. Even under the exact same conditions, there is considerable variation between individual elite athletes in fluid and electrolytes lost in sweat (Maughan et al. 2004, Shirreffs 2010).

Sweat glands can selectively reabsorb electrolytes (Taylor and Machado-Moreira 2013). As flow increases more electrolytes are lost.

Environment and workout can influence sweating.

A person wearing a heavy sweat suit running a 8 minute mile at 87 F is going to sweat more than the same person wearing shorts and lifting weights at 65 F. Anyone working out in the heat needs to make sure to rehydrate before, during and after exercise. Likewise, a 90 minute workout needs a lot more hydration than a 20 minute workout.

Fat people do not sweat more than skinny people.

Several recent studies have reported no difference in perspiration during exercise when comparing lean and obese girls (Leites et al. 2013) and higher and lower body fat men of similar fitness levels (Limbaugh et al. 2013). There does not seem to be a difference in sweat loss between lean and obese people.

Fit people sweat more than unfit people (Ichinose-Kuwahara et al. 2010).

I know that it sounds weird but sweating is your body's way of cooling itself. As people get more fit this cooling mechanism kicks in earlier and at a lower core body temperature. While this helps fit people avoid heatstroke it can also mean that you need more liquids as you get in better shape.

Men sweat more than women (I'm sure that you are not surprised).

Ichinose-Kuwahara et al. (2010) found that men sweat a lot more than women of the same fitness level. Trained women athletes had just as many sweat glands as the trained men but the women produced less sweat from each individual gland. Unfit men sweated more than unfit women. Unfit women perspired the least. Their core temperature increased by quite a lot before they started sweating.

So why do men sweat more than women? Testosterone may be to blame. Children of both sexes sweat at the same rate. Once puberty kicks in men sweat more (Araki et al. 1979, Zakas et al. 1994). Men given estrogen sweat less (Kawahata et al. 1960).

Why is sweat stinky?

There are three types of sweat; exercise, high temperature and stress sweat. Exercise and high temperature sweat are produced from eccrine gland secretions and are mostly water. These types of sweat do not stink when they are emitted. Bacteria on the skin digest sweat and secrete volatile fatty acid and sulfur compounds that make it stink later.

Stress sweat is produced from the adocrine gland. It is 20% nutrients, including fats and proteins, and 80% water. Stress sweat also produces pheromones. Needless to say, hungry skin bacteria really love to digest this sweat and make noxious smelly compounds. These are the glands that really turn on during puberty (i.e. they account for the vast difference between a sweet smelling 6 year old boy and a eye watering smell of a high school boys locker room). People who are under stress usually have a much stronger odor than those who are exercising.

One study had men smell samples of female stress sweat while watching videos of women in stress producing situations (such as giving a speech). Men rated the women in the videos lower in confidence, trustworthiness and competence while they were inhaling stress sweat compared to when they were inhaling treated sweat (antiperspirant treated) (Dalton et al. 2013). Women watching the videos identified the video subjects as stressed but did not rate them lower in confidence, trustworthiness and competence. Exercise sweat as a control but since the researchers collected it on the same day as the stress sweat they had concerns that it might have been contaminated.

Male and female sweat smell differently. The composition of the sweat itself is the same in men and women. However, two components, a volatile fatty acid, (R)/(S)-3-hydroxy-3-methylhexanoic acid ((R)/(S)-HMHA), and a volatile thiol, (R)/(S)-3-methyl-3-sulfanylhexan-1-ol ((R)/(S)-MSH), are metabolized differently in men and women. These compounds are responsible for the stinky smell of sweat (Troccaz et al. 2009).

Strong food and drink can be emitted through sweat. Some noxious odors can come from tobacco, alcohol, onions, garlic, curry and spices.

Age also makes a difference in how people sweat.

Children have immature sweat glands and are less adaptive to environmental conditions than adults (Gomes et al. 2013). This means that you should make sure that children have adequate fluids and access to a cool shady area under adverse heat or humidity (and children shouldn't be running marathons).

Sweat glands produce stem cells.

Don't hate on your sweat glands. Not only do they help cool your body but they also produce stem cells that can heal injuries and make new skin. Other sources of stem cells, such as bone marrow, can be painful and expensive to harvest. With sweat cells, a simple trip to the dermatologist for a small skin scraping can provide you with your own stem cells. These cells have been shown to promote and accelerate skin healing and grow new skin too (Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft 2014).

References

Araki T, Toda Y, Matsushita K & Tsujino A (1979). Age differences in sweating during muscular exercise. J Physical Fitness Jpn 28, 239–248. CiNii. Dalton P, Mauté C, Jaén C, Wilson T. Chemosignals of Stress Influence Social Judgments. PLoS ONE 2013;8(10): e77144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077144 (full text) Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft. (2014, February 4). Sweat glands heal injuries, source of stem cells. ScienceDaily. Retrieved February 17, 2014 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/02/140204073930.htm Gomes LHLS , Carneiro-Júnior MA, Marins JCB. Thermoregulatory responses of children exercising in a hot environment. Rev Paul Pediatr 2013;31:104-10. Full text. Ichinose-Kuwahara T, Inoue Y, Iseki Y, Hara S, Ogura Y, Kondo N. Sex differences in the effects of physical training on sweat gland responses during a graded exercise. Exp Physiol. 2010;95:1026-32. Pubmed. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2010.053710 (full text). James L. Milk protein and the restoration of fluid balance after exercise. Med Sport Sci. 2012;59:120-6. Pubmed. doi: 10.1159/000341958 James LJ, Clayton D, Evans GH. Effect of milk protein addition to a carbohydrate-electrolyte rehydration solution ingested after exercise in the heat.Br J Nutr. 2011;105:393-9. Pubmed. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510003545 James LJ, Evans GH, Madin J, Scott D, Stepney M, Harris R, Stone R, Clayton DJ. Effect of varying the concentrations of carbohydrate and milk protein in rehydration solutions ingested after exercise in the heat. Br J Nutr. 2013;110:1285-91. Pubmed. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513000536 Kawahata A. Sex differences in sweating. In Essential Problems in Climatic Physiology, ed. Ito S, Ogata H & Yoshimura H, 1960; pp. 169–184. Nankodo, Kyoto, Japan. Leites GT, Sehl PL, Cunha Gdos S, Detoni Filho A, Meyer F. Responses of obese and lean girls exercising under heat and thermoneutral conditions. J Pediatr. 2013;162:1054-60. Pubmed. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.10.047 Limbaugh JD, Wimer GS, Long LH, Baird WH. Body fatness, body core temperature, and heat loss during moderate-intensity exercise. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2013;84:1153-8. Maughan RJ, Merson SJ, Broad NP, Shirreffs SM. Fluid and electrolyte intake and loss in elite soccer players during training. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2004;14:333-46. Pubmed. Mao IF, Chen ML, Ko YC. Electrolyte loss in sweat and iodine deficiency in a hot environment. Arch Environ Health. 2001;56:271-7. Pubmed. Sharp RL. Role of sodium in fluid homeostasis with exercise. J Am Coll Nutr. 2006 Jun;25(3 Suppl):231S-239S. Pubmed. Shirreffs SM. Hydration: special issues for playing football in warm and hot environments. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20 Suppl 3:90-4. Pubmed. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01213.x Shirreffs SM, Watson P, Maughan RJ. Milk as an effective post-exercise rehydration drink. Br J Nutr. 2007;98:173-80. Pubmed. Taylor NA, Machado-Moreira CA. Regional variations in transepidermal water loss, eccrine sweat gland density, sweat secretion rates and electrolyte composition in resting and exercising humans. Extrem Physiol Med. 2013;2:4. Pubmed. doi: 10.1186/2046-7648-2-4 (full paper) Troccaz M, Borchard G, Vuilleumier C, Raviot-Derrien S, Niclass Y, Beccucci S, Starkenmann C. Gender-specific differences between the concentrations of nonvolatile (R)/(S)-3-methyl-3-sulfanylhexan-1-Ol and (R)/(S)-3-hydroxy-3-methyl-hexanoic acid odor precursors in axillary secretions. Chem Senses. 2009;34:203-10. Pubmed. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjn076 (full text) Watson P, Love TD, Maughan RJ, Shirreffs SM. A comparison of the effects of milk and a carbohydrate-electrolyte drink on the restoration of fluid balance and exercise capacity in a hot, humid environment. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:633-42. Pubmed. doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0809-4 Zakas A, Mandroukas K, Karamouzis M, Panagiotopoulou G. Physical training, growth hormone and testosterone levels and blood pressure in prepubertal, pubertal and adolescent boys. Scand J Med Sci Sports 1994;4:113–118. Wiley Online Library.